Trapped by rightness: When our instinct to believe we are right closes us off to the ways we are wrong

It feels so lovely to be certain about something—we feel clear, comfortable, even righteous. Daniel Kahneman summed up his core findings from his Nobel-prize winning work as learning that: “Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.” Because this “comforting conviction” is so widespread, it was once probably adaptive and helpful. If we thought we were wrong most of the time, we’d be paralyzed. You can imagine two of our foremothers, wandering through the jungle, hearing a crackling noise. One thinks, “That sounds like a big dangerous animal—I should run!” and she runs. The other thinks, “That sounds like a big dangerous animal, but it could be just about anything really. I don’t know, I’m never sure about these things and don’t want to leap to conclusions…” and she might be lunch.

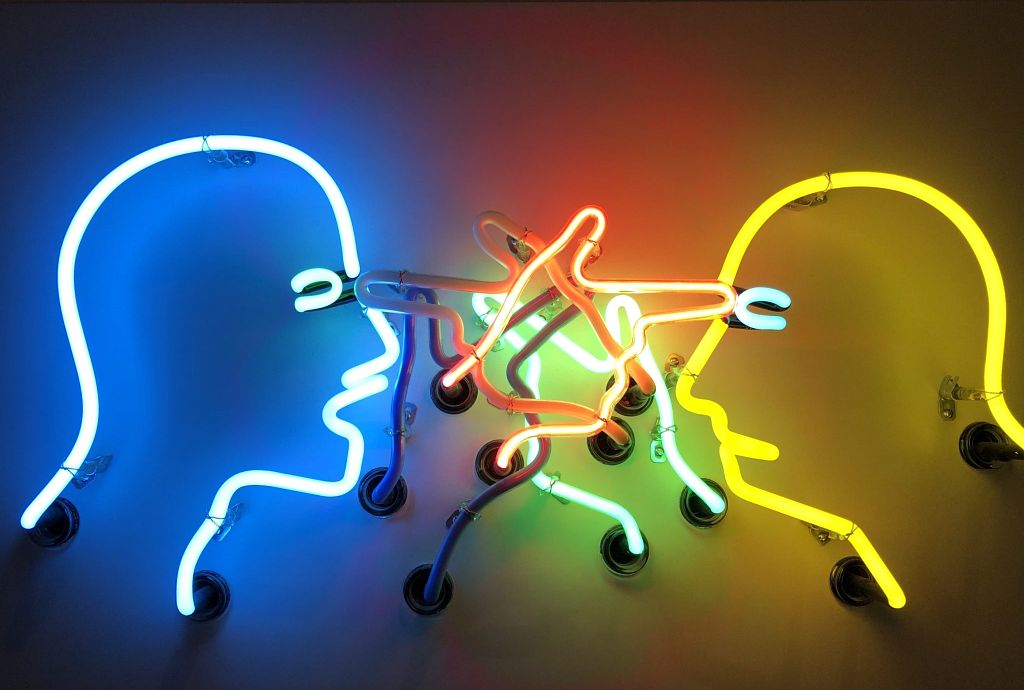

It turns out though, that this sense of certainty is a trap in complexity. The reason it’s a mindtrap is because that feeling of rightness is automatic and isn’t related to whether we are, in fact, right. The neurologist Robert Burton found that in fact the feeling of certainty was exactly that—an emotion. So what feels like the result of a logical process actually has nothing to do with logic. This means that sometimes you’ll feel right and be right and sometimes you’ll feel exactly the same way but be exactly wrong. I have a client who calls this “the rightness hangover”: it feels great in the moment but not so good the next morning.

Our feeling of rightness shapes not only what we think, but how we treat other people. If you’re open and puzzling about something and someone comes along and asks you questions about it, that seems like a great benefit (in fact, you might even pay someone to do that because it’s so helpful). If you’re sure about something and someone comes along and asks you questions about it, that seems like an annoyance.

The most important move when we are

trying to get out of the rightness trap

is to change the way we listen.

It turns out that much of the time, we listen to win. This is not because we are necessarily trying to be belligerent or to have an argument. Often, we listen to win for the nicest possible motivations. In person, it looks more like this. Your colleague/partner will say, “I’m frustrated that no one really even notices how much I contribute!” And you say, “I’m sure everyone is grateful for how good your work is!” That might be true—and sometimes it might even be helpful—but you’ve listened to what she said in order to negate it.

The second most common form of listening we think about as listening to fix. You know this one too, I’m sure. It’s when someone comes to you and you think, “Oh, I can help you with that!” So when your friend says, “I’m frustrated that no one really even notices how much I contribute,” you say something like, “Have you tried making a list of everything you’ve accomplished and letting people know?” That might be a good suggestion, and it might be helpful to the other person, too.

What these two forms of listening have in common is that they both start with our belief that we are right in some way. And it might be true. But in a world where things are moving really fast and are more complex than our brains can easily handle, these forms of listening strengthen the rightness mindtrap. What we need to escape the trap is listening to learn.

Listening to learn requires that we watch our assumption that we are right (and we can either make the problem go away by winning or make it go away by fixing) and instead believe that the other person has something to say that we don’t understand and therefore we can’t immediately help or make the problem go away. Listening to learn requires that we hold off and try to understand for a few minutes. So when you hear, “I’m frustrated that no one really even notices how much I contribute,” you could try a listening to learn move: “Hmm. So it feels like you’re contributing a lot but you don’t get any recognition?” (You have to say this in an open and curious voice, like you really are wanting to learn, or else it can come across as snarky.) Then your colleague/partner/friend might say, “Yes, totally!” or “Well, that’s just it. I’m not even sure that I am contributing because I never get any feedback.” Or “Kind of. I guess I’m wondering whether I rely too much on the feedback of others rather than really knowing in myself what good work looks like.” Or something else. The point is that if you don’t believe you’re right from the outset, you might find yourself hearing things that open up whole new possibilities for solutions.

See, when we think we’re right, we narrow and close down possibilities. And mostly we don’t even notice we’re doing that—that’s why it’s a mind trap. But if we hold the possibility that we might be wrong, whole new vistas open for us. We become more curious, better listeners, and better problem solvers.

See more (including the other four mindtraps and ways to escape them) in my Unlocking Leadership Mindtraps: How to Thrive in Complexity.

Subscribe via Email