One of the maxims taught to young journalists is that all news is local. It is also most powerful when it is personal.

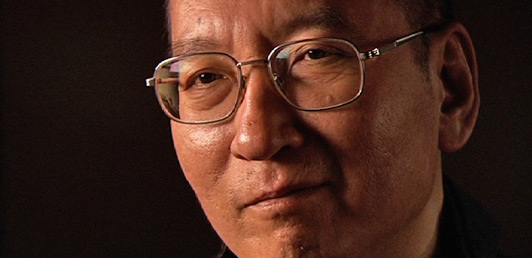

Liu Xiaobo died yesterday in captivity. The Nobel-prizewinning Chinese human rights activist had been in prison for the past eleven years after his calls for democratic reform in China led to a conviction for inciting subversion. He died riddled with liver cancer but not released from custody. Ironic that he died the day before Bastille Day – a commemoration of democratic ideals and, given what followed, a reminder of how ugly change and revolutions can be. The struggle for human rights and human liberation is messy and long.

The personal connection arose while reading Liu Xiaobo’s obituaries. He and I were born on the same day, December 28, 1955. This fact is irrelevant to everyone but me but it made his death more moving and more personal. I have a felt experience of the full span of his life and I am even more impressed about what he achieved in his (short) span.

His death is a reminder of how fragile democratic practices and processes really are. I have been blessed to have been born and live in one of only perhaps seven or eight countries where representative democracies have functioned uninterrupted since the turn of the past century, and, in New Zealand’s case, we have had almost full suffrage from that time.

Democracy advanced on many fronts at times over the past 117 years. We have tended to imagine, despite the evidence to the contrary, that this advance of democracy is a one-way street. In many places democracy is in reverse. It is being chipped away at now in disturbing ways.

Because the United States has gone AWOL, we now look to for international leadership on issues such as climate change, to China. It is a behemoth. It needs to be at the table. And it is a dictatorial one-party state, as demonstrated by Liu Xiaobo’s death. India is showing trends of state-supported Hindu nationalism. In Russia kleptocracy is on the rise. Turkey is voting itself to dictatorial rule. The list goes on.

Liu Xiaobo’s death is a reminder of the special blessings of democracy in its most open and inclusive sense and how fragile that can be. Informed democracies, healthy inclusive communities, public participation in decisions, respect for the rule of law, respect for diverse views, freedom of expression, a free and effective media that can investigate and question — these are all part of a network of elements that needs to be nurtured and defended to create or maintain a healthy democratic society. These elements inevitably compromise the exercise of power and the unfettered enjoyment of excessive wealth.

There are ways these elements are supportive and the system can be self-organising but it is also very vulnerable to degenerative diseases. Inclusive democracies function as a big system that needs constant vigilance.

Too many of us have taken it for granted for too long that these democratic systems are self-organising and self-maintaining. The challenges visible to us now, the challenge posed in Liu Xiaobo’s death, are that we need to DO democracy not HAVE it.

Subscribe via Email