Packing, cracking, and the shallow state

Every boundary redrawing process is perfectly designed to create the electoral districts it creates.

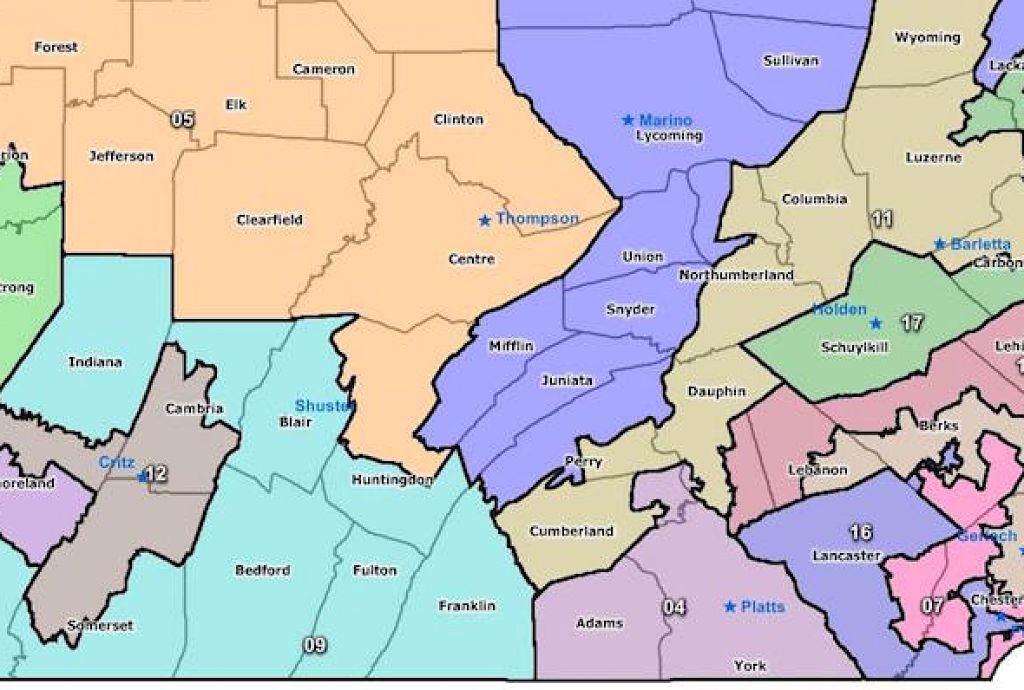

When I look at a map of Pennsylvania’s congressional districts, particularly those in the southwest and southeast of the state, it is as through it were constructed by a group of pasta makers fortified by gallons of Chianti Classico. Farfalle bowties were laid down for districts 18 and 12 with a ravioli for the centre of Pittsburgh. Big orecchiette ears for districts 9 and 16. By the time they got to the areas around Philadelphia they must have been totally sozzled: for 6, &, and 13 they entangled cavatappi corkscrews and then threw tagliatelle at the wall for districts north of the city.

Would that it were so innocent. Take a closer look at District 7. How is that a coherent electorate? It is not. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court said the state’s re-districting “clearly, plainly, and palpably,” violated the Pennsylvanian constitution when it recently struck down the state’s congressional map.

This is gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral boundaries to favour one side over the other. The name comes from a Boston newspaper’s description of efforts in the early 19th century by Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry to redraw a district’s boundaries in his party’s favour ending up with something resembling a salamander.

The practice has a long history, especially in the United States. It is a great example of Paul Batalden’s epigram: every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. Every boundary redrawing process is perfectly designed to create the electoral districts it creates.

Gerrymandering involves packing and cracking. Packing means making sure as many of the opposition voters are packed into as few electorates as possible. Cracking is distributing the opposition voters so they make up a minority across many electorates. These two tools can ensure that even if the popular vote in an election is lost, the party that controls the redrawing process can still achieve a comfortable victory.

I have been wondering about the systemic aspect to this. The process fascinates me because I live in a little democracy where this does not happen. The New Zealand re-districting system is not perfect but our electorates tend to look more like blobs of tortellini or rectangles of lasagne. They are relatively coherent representations of communities re-designed every five years by an independent commission led by a judge and including senior government officials (such as the Surveyor General, the Chief Statistician, and the Chief Electoral Officer) and representatives of political parties. There are arguments at the margins but little suggestion of gerrymandering. Political parties are involved but they do not control the process or decide the outcome as in most US states.

What is it about the US system that makes gerrymandering so much more prevalent? Francis Fukuyama provides an insight in Political Order and Political Decay, the second volume of his work on the emergence of political order in our societies. His argument in general is that effective political systems need to balance a strong state, rule of law, and accountability to the broader community. His argument about the US is that it has a weak state and too many of the state functions in other democracies end up being exercised in the US between the legislature (part of the accountability system) and the courts which are not suited to resolving complex case-by-case issues.

The US Constitution effectively puts the drawing of electoral boundaries in the hands of state legislative majorities (allowing them to draw and re-draw to their advantage) rather than with independent bodies. This leaves the courts to arbitrate on disputes. The independent redistricting commission in Arizona survived a challenge in the US Supreme Court in 2015 when a majority of justices accepted the argument that the commission was an extension of the state legislature because it had been established as the result of a referendum.

Systems shape results. The US Constitution was deliberately designed by the Founders to constrain the power of the state. Ever since there have been arguments about its interpretation. In the case of electoral boundaries, we can see how a system built around reserving power for legislatures to make the decisions can then struggle when it comes to governing the establishment of legislative bodies. Political majorities have massive vested interests in shaping the system to work for their tribe or party. This power can be checked by courts but the process of balancing of power in the system can also create whiplash or fishtailing amplifying uncertainties and encouraging more partisan responses on all sides. Going back and forth between one body led by my tribe to another body led by theirs creates a set of reinforcing feedbacks. If we do not nail home our advantage here and now then the other side will rip it away from us over there in the future! These feedbacks are amplified in our much more data-rich world where voter inclinations can be mapped with much greater precision and gerrymandering can be even more powerful.

BTW: There is an element of tit for tat in the Pennsylvanian case. A Republican majority in the legislature approved the gerrymandered electoral map and then the state Supreme Court decided 5-2 to reject that map. The Court’s vote was divided along party lines with Democratic justices in the majority and Republicans in dissent.

The New Zealand system is similar to many other Western democracies. In general, these tend to have “deeper states” than the USA. These countries tend to use commissions as arms of the state to reach independent decisions on electoral boundaries. In systemic terms these commissions dampen down the advantages that might accrue to political parties and remove much of the gaming of the system.

Some argue that these countries lack the freedom that is enshrined in the American Constitution. Perhaps they do lack some of those specific freedoms. They also lack the perverse gerrymandering that is a consequence of ways the US freedoms have been articulated. My sense is many of these other countries arrive at their freedoms by different democratic routes and using different systems. Take your pick.

Subscribe via Email